A Comparison of Portable Solar Generator Capacity, Inverter Ratings, and Battery Types for Off-Grid Boondocking

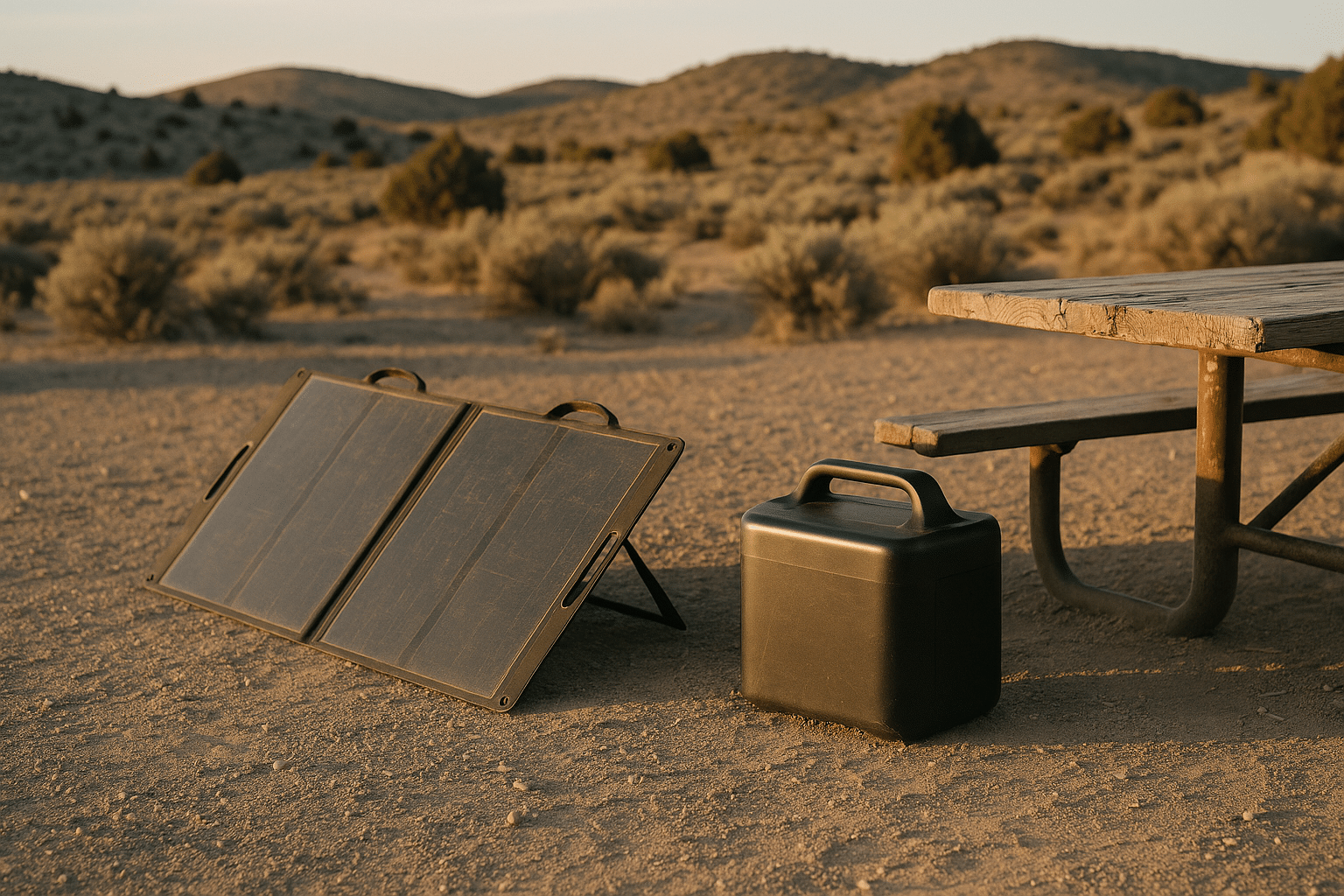

Heading into the backcountry is easier when your power plan makes sense. Portable solar generators combine a battery, inverter, and charge controller in a single box, but their spec sheets can be confusing—capacity in watt-hours, inverters with continuous and surge ratings, and battery chemistries with trade-offs in weight, lifespan, and safety. This article compares these elements with plain numbers and real-world examples so you can confidently match a setup to your off-grid boondocking style.

We’ll keep it practical: estimate your daily energy use, translate that into a right-sized generator, align the inverter to your actual appliances, and choose a battery chemistry that fits your climate, budget, and cycle life expectations. Along the way you’ll find simple rules of thumb for solar panel sizing, pointers to avoid inefficient conversions, and a few field notes from common camping scenarios. Let’s turn scattered specs into a reliable system that quietly works while you enjoy the view.

Outline: How This Comparison Helps You Choose Wisely

This outline lays the roadmap for the decisions that matter when you’re unplugged and parked on a forest road or desert wash. The goal is to show how generator capacity, inverter ratings, and battery types interact, so you avoid paying for capability you won’t use—or worse, discovering limitations after sundown. Each subsequent section builds from energy budgeting to component sizing, then zooms into battery chemistry and, finally, turns all the pieces into practical kits for different boondocking styles.

What’s inside this guide:

- Section 1 (you’re here): The outline itself—why capacity, inverter, and battery chemistry must be thought of as a matched set, not isolated checkboxes.

- Section 2: Capacity and energy budgeting. You’ll learn how to tally daily watt-hours, account for conversion losses, and choose a generator size that can ride out cloudy spells.

- Section 3: Inverter ratings explained. We’ll unpack continuous versus surge power, waveform quality, idle draw, and which household devices are realistic off-grid.

- Section 4: Battery chemistry compared. Lithium iron phosphate, nickel manganese cobalt, and sealed lead-acid each have distinctive strengths; we’ll translate those into camping outcomes.

- Section 5: Putting it together. Real-world kits matched to weekenders, remote workers, and long-haulers, plus solar input guidelines and a concise conclusion.

How to use this guide in the field:

- Skim the energy budget steps with your own gear list and modify the examples to reflect your usage hours.

- Check inverter needs by looking at appliance labels and, when possible, measuring actual draw with a plug-in meter before your trip.

- Choose a battery chemistry based on climate (especially cold charging), expected cycle count, and how much mass you are comfortable hauling.

- Align solar panel wattage with your daily refill target and local peak sun hours to sustain your routine without running short.

By the end, you’ll be able to read a spec sheet with context, understand where bottlenecks occur, and pick a balanced system—one that charges predictably, powers your essentials, and doesn’t weigh down the adventure.

Capacity, Usable Energy, and an Honest Boondocking Energy Budget

Capacity is the anchor for every decision you’ll make. Portable solar generators typically list capacity in watt-hours (Wh). That number reflects how much energy the internal battery can store, but usable energy is always lower due to inverter losses, battery management overhead, and temperature effects. As a rough rule, assume 85–90% of listed capacity is available for AC loads, and 90–95% for DC loads. Planning with conservative margins keeps your lights on when weather or usage varies.

Start with an energy budget: list devices, their average power, and hours per day. A sample minimalist boondocking day might look like this:

- 12V compressor fridge: 25–45 W average, 24 h cycling = 300–600 Wh/day depending on ambient heat and insulation.

- LED lights: 5–15 W for 4 h = 20–60 Wh.

- Vent fan: 12–30 W for 4 h = 50–120 Wh.

- Water pump: ~70 W, 10 minutes total = ~12 Wh.

- Laptop: 40–70 W while charging, 1.5 h = 60–105 Wh.

- Phone/USB devices: 10–20 Wh.

Total: roughly 460–915 Wh/day. Add a 10–20% buffer for inverter overhead and variability, and your daily target is ~550–1,100 Wh. That sets expectations for capacity and solar replenishment. For weekend trips, a 1,000–1,500 Wh unit can be comfortable without heavy solar, especially if you arrive with a full battery. For longer stays, the solar input must meet or exceed daily consumption to avoid gradual depletion.

Translating this into generator sizes:

- Day trips or minimal loads (no fridge): 300–600 Wh capacity; a 100 W panel can replace 200–400 Wh on a sunny day in many regions.

- Weekend with fridge and light work: 1,000–1,500 Wh; plan on 200–300 W of solar to recover ~600–1,000 Wh/day with favorable sun.

- One-week stays, heavier device use: 2,000–3,000 Wh; 300–600 W of solar helps sustain 1–2 kWh/day, acknowledging weather swings.

Depth-of-discharge also matters. Lithium chemistries commonly deliver 80–90% usable capacity without accelerated wear, while sealed lead-acid is far happier at ~50% cycling. If you must ride through a cloudy stretch, that usage margin can make the difference between cold food and warm drinks. Finally, consider parasitic loads: inverter standby can be 5–20 W; that’s 120–480 Wh wasted over 24 hours if left on. When practical, use DC outputs for fridges and devices, and power the inverter only when AC is needed. These small choices stretch capacity and reduce the solar you must carry.

Inverter Ratings Decoded: Continuous, Surge, Waveform, and Efficiency

The inverter turns your battery’s DC power into household-style AC, and its rating caps what you can run. Two numbers dominate spec sheets: continuous power (what it can deliver indefinitely at a given temperature) and surge power (short bursts to start motors or compressors, usually 2–3 seconds). For boondocking, the continuous rating governs devices like induction plates or coffee makers, while surge handles the momentary peak when a fridge or blender kicks on.

What do common appliances demand?

- Laptop chargers: 45–100 W; little surge.

- TVs and routers: 20–120 W total; steady draw.

- CPAP machines: 30–70 W without heated humidifier; add 50–150 W with the heater on.

- Microwaves: “700 W cooking output” may pull 1,000–1,200 W from AC due to magnetron inefficiency.

- Drip coffee makers: 700–1,000 W; short duty cycle.

- Hair dryers: 1,000–1,600 W; very heavy for small systems.

- Small power tools: 300–800 W with brief surges when starting.

Match the inverter to the heaviest single device you intend to use, then verify surge headroom. If you need 1,000–1,200 W continuous for a microwave, that generally calls for a 1,500–2,000 W inverter so you’re not operating on the edge. Compressor devices (fridges, some fans) can spike 2–3x their running wattage; an inverter with robust surge overhead prevents nuisance shutdowns. Waveform matters, too. Pure sine wave output plays nicely with sensitive electronics and induction motors, minimizing heat and audible buzz, while modified waveforms can be cheaper but may cause inefficiency or noise in some devices.

Efficiency and idle draw shape your energy budget more than you might think. Many integrated inverters run at 85–92% efficiency near their sweet spot, but part-load efficiency can drop, and standby draw can quietly sip 5–20 W. Practical tips:

- Use DC ports for DC-native gear (12V fridges, USB chargers) to skip conversion losses.

- Group AC tasks. Brew coffee, charge power tool batteries, and microwave while the inverter is awake, then shut it down.

- Check temperature derating: inverters reduce output as temperatures rise; ventilate the unit and avoid burying it under bedding.

In short, buy for your real loads, not hypothetical ones. A right-sized 600–1,000 W inverter handles laptops, small kitchen tools, and many essentials. Jump to 1,500–2,000 W if you’re committed to microwaving or running multiple AC devices at once. Avoid oversizing too far; larger inverters often mean higher idle consumption and faster battery drain for the same tasks.

Battery Chemistry Compared: LFP vs. NMC vs. Sealed Lead-Acid (AGM/Gel)

The heart of a portable generator is its battery chemistry. Each option trades off energy density, cycle life, weight, safety, cold-weather behavior, and cost. Understanding these differences turns a spec sheet into meaningful choices rather than alphabet soup.

Lithium iron phosphate (LFP):

- Cycle life: commonly 2,000–4,000 cycles to ~80% capacity at moderate depth-of-discharge, making it well-suited for frequent use.

- Safety: thermally stable and generally considered more tolerant under abuse compared to other lithium blends.

- Weight and volume: lower energy density than some lithium variants, so a given Wh may weigh more and take more space.

- Cold charging: avoid charging below ~0°C (32°F) unless the pack includes heating and proper management; discharging in the cold is usually acceptable.

- Voltage behavior: flat discharge curve means steadier output voltage under load, helpful for DC appliances.

Nickel manganese cobalt (NMC):

- Cycle life: typically ~500–1,000 cycles to ~80% capacity at similar depth-of-discharge, which is fine for occasional camping but less ideal for daily cycling.

- Energy density: higher Wh per kilogram than LFP, resulting in lighter packs for the same capacity.

- Cold behavior: often more tolerant of low-temperature charging than LFP, but still benefits from warm-up and careful management.

- Safety: requires robust battery management; reputable designs include protections for overcurrent, overvoltage, and thermal events.

Sealed lead-acid (AGM/gel):

- Cycle life: around 200–500 cycles when limited to 50% depth-of-discharge; deep cycles shorten life considerably.

- Weight: very heavy for the energy delivered; a 1 kWh lead system can weigh multiple times an equivalent lithium pack.

- Charge acceptance: slower bulk charging and reduced usable capacity at high discharge rates (Peukert effect) complicate daily replenishment.

- Temperature: more forgiving to charge in the cold than many lithium chemistries, but overall lifespan still suffers in extreme temperatures.

What should boondockers pick?

- Frequent off-grid use, long-term value, safety focus: LFP is well-regarded for its cycle life and predictable performance.

- Weight-sensitive setups where the pack is used occasionally: NMC can offer lighter carry for the same capacity, with shorter cycle life.

- Budget-constrained, stationary, or backup-only roles: AGM/gel can work, but plan for higher mass, lower usable capacity, and careful charge management.

Beyond chemistry, check the battery management system (BMS) limits: maximum discharge power, allowable charging current, low-temp protections, and cell balancing. These hard caps directly affect whether your inverter can deliver its nameplate power and how quickly solar can refill the tank. Chemistry sets the character; BMS sets the rules. Make sure those rules match your gear and your climate.

Putting It Together: Matched Systems, Solar Refill, and a Field-Focused Conclusion

Now that capacity, inverter ratings, and chemistry are clear, let’s translate them into cohesive kits. The key is balance: battery big enough for your daily routine, inverter sized to the heaviest appliance you actually use, and solar input aligned with your average consumption plus a buffer for inefficiencies and weather.

Example kits and what they support:

- Compact day-to-weekend kit: ~1,000 Wh LFP/NMC, 600–1,000 W inverter, 150–250 W solar. Handles a 12V fridge, lights, fan, laptops, and brief microwave use if you manage sequence and watch state of charge. Expect ~500–800 Wh/day harvest in sunny regions (4–5 peak sun hours) with a high-quality MPPT controller and tidy wiring.

- Work-and-wander kit: ~2,000 Wh LFP, 1,500 W inverter, 300–400 W solar. Add steady laptop time, camera charging, and occasional coffee maker use. Daily harvest of ~1–1.5 kWh in good conditions keeps you net-neutral; two cloudy days may require conservation or a supplemental charge.

- Extended-stay kit: ~3,000–4,000 Wh LFP, 2,000 W inverter, 500–800 W solar. Supports a couple sharing a fridge, devices, fan, and regular microwave use. You’ll carry more panel area and mass, but your autonomy improves notably when skies cooperate.

Solar math shortcut: in many North American boondocking spots, 1 W of panel yields roughly 4–6 Wh per clear day. Multiply panel watts by local peak sun hours and by a system efficiency factor (0.6–0.75) to set expectations. Replenishing 1,000 Wh daily may require ~300 W of panels in excellent sun or 400–500 W in mixed conditions. Aim to recover your daily budget by mid-afternoon; that cushion absorbs shade shifts and late-day clouds.

Quality-of-life considerations:

- Keep the inverter off until you need AC; rely on DC ports for routine charging to cut standby losses.

- Ventilate your power station; heat reduces output and shortens inverter lifespan.

- Plan for cold. If you camp below freezing, choose LFP with managed low-temp charging or an alternative chemistry that tolerates cold charge better.

- Distribute loads over time. High simultaneous draw stresses the inverter and can trip BMS limits even when capacity remains.

Conclusion for boondockers: treat the spec sheet as a system, not a shopping list. Start with your daily watt-hours, pick a battery chemistry that fits your climate and cycle expectations, size the inverter to the real peak device you intend to run, and give your solar enough headroom to refill the tank most days. A balanced 1–1.5 kWh setup satisfies many weekenders; remote workers and couples who cook electrically often appreciate 2–3 kWh plus 300–600 W of panels. Build conservatively, measure your actual usage, and let your power system fade into the background while the trip takes center stage.