RV Air Conditioner Power Requirements and Solar Panel Sizing for Daily Use

Outline:

– Power planning importance and key terms

– What RV ACs actually draw: running, surge, duty cycles, inverter and generator considerations

– Solar and battery sizing method: build an energy budget, convert cooling hours to watt-hours, translate sun hours to panel watts

– Realistic scenarios for mild, warm, and hot climates, with sample arrays and storage

– Practical installation, efficiency upgrades, and a traveler-focused conclusion

Why RV AC Power Planning Matters

On the road, cool air feels like a luxury—until the thermometer climbs and it becomes essential for comfort and safety. RV air conditioners are among the largest electrical loads in a mobile home, and their needs don’t always fit neatly into small battery banks and modest rooftop solar arrays. That mismatch is why careful planning pays off. The goal isn’t just to run an air conditioner; it’s to do it predictably, without draining batteries prematurely or relying entirely on plug‑in power. A thoughtful plan lets you balance comfort, energy supply, and the realities of sunshine and space.

Before diving into numbers, it helps to align on a few basics. Think of power as the immediate demand (watts) and energy as the total work over time (watt‑hours). An RV air conditioner’s label often shows cooling capacity in BTU, but what matters to your batteries and panels is the electrical draw. Here are compact definitions you’ll use throughout the article:

– Watts (W): instantaneous power draw.

– Watt‑hours (Wh) or kilowatt‑hours (kWh): energy used over time.

– Amps (A): current; at 120 V AC, Watts ≈ Volts × Amps.

– Duty cycle: percentage of time the compressor runs within a period.

Typical rooftop units range from about 9,000 to 15,000 BTU. Running power for common 13,500 BTU models often lands around 1,300–1,800 W, with larger units reaching 1,500–2,000 W or more. The compressor doesn’t run continuously; it cycles on and off, so average power over an hour can be substantially less than the running wattage. However, startup surges—brief spikes when the compressor kicks on—commonly reach 2–3× the running load, and in some cases even higher. Those short bursts drive the choice of inverter size and influence battery stress.

In practice, that means daily air‑conditioning comes down to a set of trade‑offs: how many hours you want cool air, how hot it is outside, how well your rig is insulated, and how much roof space you can devote to solar. Solar works wonderfully when expectations match the environment. If you’re chasing summer sun in wide‑open deserts, you’ll gather plenty of energy but also face heavy cooling demands. If you’re drifting along breezy coasts, your energy harvest and cooling needs could both be moderate. Understanding that balance is the first step to turning sunlight into comfort with fewer surprises.

What RV Air Conditioners Actually Draw: Running, Surge, and Duty Cycles

Power numbers on spec sheets can feel abstract until you attach them to real‑world behavior. A mid‑size rooftop air conditioner (around 13,500 BTU) commonly draws in the range of 1,300–1,800 W while the compressor is running; a 15,000 BTU unit may sit closer to 1,500–2,000 W. Fan‑only mode is far lighter, often a few hundred watts or less. The challenge is the compressor startup. For a fraction of a second, the motor demands much higher current—often 2–3× the running watts. If the running draw is 1,600 W, the startup moment might touch 3,200–4,800 W. Inverters, batteries, and wiring must tolerate that spike without tripping or voltage sagging.

Two concepts help manage this peak: inverter surge capacity and soft‑start technology. Many mobile inverters can deliver a higher surge output briefly; this headroom is essential for compressor loads. Soft‑start devices, when compatible and properly installed, can reduce the magnitude of the initial spike, lowering stress on the inverter and battery. Regardless of approach, design for both the steady load and the peak. Undersizing here often shows up as nuisance shutdowns at the least convenient time—hot afternoons.

Duty cycle adds another layer of nuance. The compressor cycles on and off to maintain the set temperature. On a mild day, you might see a 30–40% duty cycle; in hot, humid conditions, 60–80% is plausible. Average power is roughly running watts × duty cycle. For example:

– Running draw: 1,600 W

– Duty cycle: 50%

– Average over an hour: about 800 W

– Energy in 4 hours of cooling: 3.2 kWh

The numbers shift with weather, insulation, shade, airflow, and setpoint. Improving any of these reduces how long the compressor runs, cutting total energy use. For wiring and safety, assume continuous ratings for conductors and breakers that meet code, and leave margin. On the DC side, large inverters feeding air conditioners at 12 V pull high currents—easily over 150 A at full tilt. That makes short, appropriately sized cables and solid connections essential to avoid voltage drop and heat. Designing for surge, realistic duty cycles, and robust wiring transforms “maybe it’ll hold” into predictable comfort.

Solar and Battery Sizing: From Cooling Hours to Panel Watts

Right‑sizing solar for daily air‑conditioning starts with an energy budget. First, estimate how many hours per day you need cooling and what duty cycle is realistic for your climate. Then translate that into watt‑hours. Finally, map your energy need to panel wattage using local sun hours and a system efficiency factor to account for inverter losses, temperature, wiring, shading, and charge controller behavior.

Step 1: Estimate AC energy. Suppose a 13,500 BTU unit draws 1,600 W while running. If your expected duty cycle is 50% for 6 hours of comfort, the average draw is 800 W. Over 6 hours, that’s 4.8 kWh. Add other loads—fridge, lights, fans, electronics. Let’s say they total 0.7 kWh. The day’s budget becomes 5.5 kWh.

Step 2: Convert sunshine to daily energy. Solar production depends on peak sun hours (PSH)—roughly the equivalent hours per day when irradiance averages 1,000 W/m². Many parts of North America see:

– 3–4 PSH in shoulder seasons or cloudy regions

– 4–6 PSH in sunny seasons and open latitudes

– 6–7 PSH in exceptional summer conditions

Step 3: Account for system efficiency. A practical rule of thumb is that only about 70–80% of nameplate panel energy turns into stored or usable AC energy after factoring temperature, wiring, dust, inverter losses, and controller behavior. Using 75% keeps estimates grounded.

Now size the array. With a 5.5 kWh daily need, 5 PSH, and 75% system efficiency, required array power is:

– Required watts ≈ Daily kWh ÷ (PSH × efficiency)

– ≈ 5,500 Wh ÷ (5 × 0.75) ≈ 1,467 W of panels

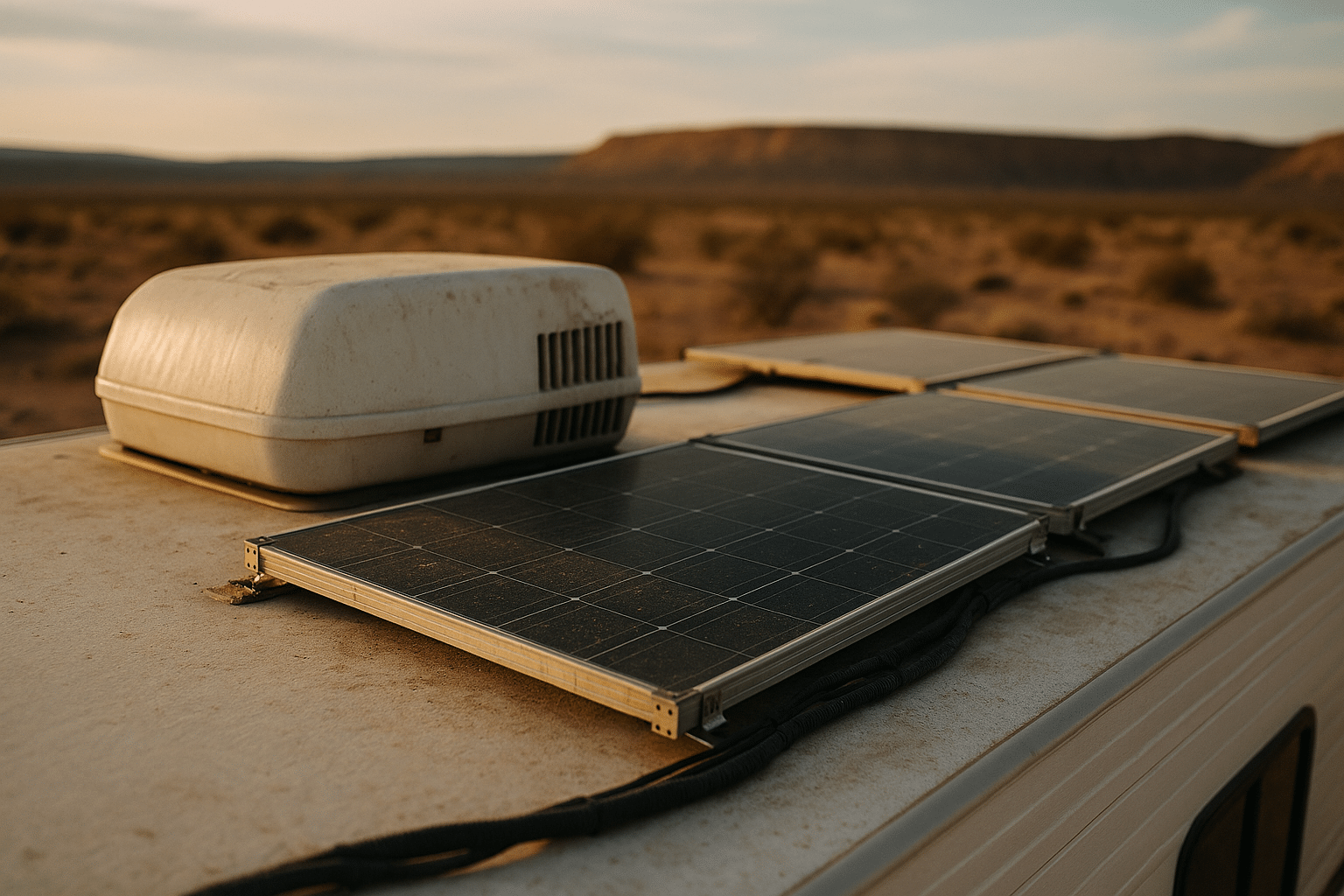

That’s a sizable roof commitment. Many RV roofs fit 600–1,200 W of panels without elaborate racks. If your roof caps at 1,000 W, and you still want 6 hours of cooling on warm days, you’ll likely need to:

– Reduce cooling hours or nudge the setpoint upward

– Improve insulation, shade, and airflow to cut duty cycle

– Add portable panels or a tilting mount when stationary

– Use a larger battery bank to shift some energy from earlier hours

– Supplement with alternator charging or occasional generator time

Batteries bridge clouds, shade, and evening cooling. For reference:

– 12 V, 100 Ah lithium: ~1.2–1.3 kWh usable

– 12 V, 100 Ah lead‑acid: ~0.5–0.6 kWh usable (at ~50% depth of discharge)

– 24 V or 48 V systems reduce current and cable size for the same power

If your AC plan calls for 4–6 kWh per day, a bank in the 300–500 Ah range at 12 V (or proportionally smaller at higher voltage) is a common target for lithium chemistry. The exact size depends on how much reserve you want for cloudy spells and whether you prefer daytime cooling powered mostly by panels or evening sessions leaning on stored energy. The key is to align roof space, climate, and expectations—then let the math steer the build.

Real‑World Scenarios: Mild, Warm, and Hot‑Weather Setups

Numbers become meaningful when they meet real trips. Consider three scenarios that reflect common travel patterns, using the same straightforward math to guide choices.

Scenario A: Mild coastal loop. Daytime highs hover around 78°F with decent breeze. A 13,500 BTU unit runs at 1,500 W while on, averaging a 35% duty cycle for 3 hours mid‑afternoon. Energy for cooling: 1,500 W × 0.35 × 3 h ≈ 1.6 kWh. Add 0.8 kWh for everything else, and the day totals 2.4 kWh. With 4.5 PSH and 75% system efficiency:

– Array ≈ 2,400 Wh ÷ (4.5 × 0.75) ≈ 711 W

– Practical roof target: 700–800 W

– Battery: 200–300 Ah at 12 V lithium (or equivalent) offers comfortable headroom

Scenario B: Warm inland valleys. Highs near 90–95°F. The same AC draws 1,600 W with a 55% duty cycle for 5 hours (some pre‑cooling plus late‑afternoon). Cooling energy: 1,600 W × 0.55 × 5 h ≈ 4.4 kWh. House loads: 0.9 kWh. Total: 5.3 kWh. With 5.5 PSH and 75% efficiency:

– Array ≈ 5,300 Wh ÷ (5.5 × 0.75) ≈ 1,284 W

– Practical roof target: 1,200–1,400 W if space allows

– Battery: 300–400 Ah at 12 V lithium helps ride out overcast days

Scenario C: Hot desert boondocking. Highs around 105°F with sun glare and minimal shade. Assume 1,700 W running draw, 70% duty cycle for 6 hours. Cooling energy: 1,700 W × 0.70 × 6 h ≈ 7.14 kWh. House loads: 1.0 kWh. Total: 8.14 kWh. With 6.5 PSH and 75% efficiency:

– Array ≈ 8,140 Wh ÷ (6.5 × 0.75) ≈ 1,671 W

– Practical roof target: 1,600–1,900 W (tilt or portable panels may be needed)

– Battery: 400–600 Ah at 12 V lithium or a higher‑voltage bank to reduce current

Across all scenarios, the inverter must handle startup surges. Aim for continuous AC output that exceeds the running draw and surge capacity that covers 2–3× compressors. On the DC side, 12 V systems can push very high currents at these loads; moving to 24 V or 48 V reduces current and cable thickness, improving efficiency. Heat management matters, too; high temperatures reduce panel output and increase cooling demand, a double hit that argues for extra capacity in hot climates.

What if your roof can only fit 800–1,000 W of panels? It’s still workable for mild to moderately warm trips if you fine‑tune operations:

– Cool the cabin earlier in the day when panel output is strongest

– Use shade, reflective covers, and ventilation to lower the duty cycle

– Accept shorter cooling windows on cloudy days

– Add portable panels to harvest shoulder‑hour sun

– Use alternator charging during drive days to replenish the bank

These examples show a pattern: calculate your cooling energy first, then see if the roof and battery plan can meet it. When they don’t align, adjust operating hours, efficiency upgrades, or charging sources. The result is a setup that feels deliberate rather than improvised.

Practical Tips, Efficiency Upgrades, and a Traveler‑Focused Conclusion

Turning the math into a satisfying day at camp comes down to practical details. Start with the low‑hanging fruit: reduce heat gain and improve airflow so your compressor works less. Shade, ventilation, and insulation make a surprising difference. Reflective window coverings, insulated skylight plugs, and exterior shade awnings tame solar gain. Sealing air leaks keeps conditioned air inside. Gentle ceiling fans and open roof vents in the morning move hot air out before cooling hours begin. Every minute the compressor rests is energy saved for later.

Panel positioning and maintenance add quiet performance gains. Rooftop arrays laid flat are convenient, but tilting toward the sun in winter or at high latitudes can reclaim 10–25% more energy on clear days. Dust and pollen can shave off several percent of output; a soft brush and water rinse restore glass clarity. Cable runs should be short and appropriately sized to limit voltage drop. On the inverter side, aim for a unit with healthy surge capacity, and consider a soft‑start device if compatible to tame those initial spikes. Batteries appreciate moderate temperatures and proper charge profiles; set absorption and float values per chemistry to extend life.

For resilience, diversify your charging sources. A DC‑DC charger tied to the alternator can push a meaningful amount of energy into the bank during travel days, easing solar reliance. Portable panels stretch capture into shoulder hours and shady camps. If your journey includes heat waves or tree‑covered sites, a small generator used strategically—say, for pre‑cooling or bulk charging—can be a reasonable backup. The goal isn’t purity; it’s dependable comfort with minimal fuel and noise.

To pull this together, here’s a concise checklist:

– Define your target cooling hours at realistic duty cycles for your climate.

– Calculate daily kWh for cooling plus house loads.

– Size panels with PSH and 70–80% system efficiency in mind.

– Choose an inverter that covers both running and surge demands.

– Right‑size the battery to buffer clouds, evenings, and travel days.

Conclusion for travelers: daily air‑conditioning from solar is achievable when expectations match physics. In coastal or shoulder‑season travel, 700–1,000 W of panels with a mid‑size lithium bank can deliver comfortable afternoon cooling. In hot interiors or deserts, plan on 1,200–1,800 W of panels and larger storage—or blend in alternator and occasional generator use. Think of your system as a living companion: it performs beautifully when you work with the weather, manage heat gain, and schedule cooling during peak sun. Build it once with clear numbers, and you’ll spend more time enjoying the breeze and less time watching gauges.